By Linda Dennis

This is the full text of Linda’s presentation on Australian wombats, an edited version of which appears in the November 2012 issue of ‘Burke’s Backyard’ magazine. The full list of contacts and further reading is at the end of this fact sheet.

Wombats have been described as ‘The Hobbits of the Australian bush’. They are secretive creatures who spend most of their time asleep underground, venturing out in the cool, dark of night.

Because they are rarely seen wombats remain a mystery to most people. There are many Australians who have never even seen a wombat in the wild. The wombat is certainly one of Australia’s lesser known marsupials, unlike the koala and kangaroo.

Three species

Australia has three species of wombat: the bare-nosed wombat also known as the common wombat (Vombatus ursinus), the southern hairy-nosed wombat (Lasiorhinus latrifons), and the northern hairy-nosed wombat (Lasiorhinus krefftii), also known as yaminon.

All three species of wombat are in trouble, facing many and varied threats – and some of these threats are more severe than others.

Northern hairy-nosed wombats

The northern hairy-nosed wombat – Australia’s second most endangered animal – is at the top of the concern list. Ironically, it is also considered the most secure of the three species as much work has been done – and is being done – to save the species from tipping over the edge to extinction.

In the entire world there are only 138 northern hairy-nosed wombats left. The species is classified as endangered by the Australian Federal Government and in classed as ‘critically endangered’ on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. There are no northern hairy-nosed wombats in captivity and there are only two wild populations: one is in central Qld, at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) near Clermont; and the other is at The Richard Underwood Nature Refuge near St George in Southern Qld.

It is thought that the northern hairy-nosed wombat was already a rare species at the time of European settlement, although it could be found in pockets of inland Eastern Australia from Vic to Qld. After European settlement the species declined due to habitat loss, farming and predation. By the mid 1970s it was estimated that there were only 35 individuals left in one single population at Epping Forest.

With the implementation of The Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage Protection (EHP) Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat Recovery Plan, which included projects such as the erection of the wild dog fence and the installation of water and feed troughs through the park, the species saw a slow but steady increase.

In 2000 the first northern hairy-nosed wombat ‘hair census’ was conducted, where hair samples were collected (using double-sided sticky tape traps at burrow entrances) and DNA extracted to determine the number of individuals in the population – there were 113 at that count.

Unfortunately, in the same year, a pack of dogs entered the area and at least 10 wombat individuals were killed. A 20 kilometre wild dog fence was erected as a result.

Eager volunteers from around the globe helped to conduct a hair census every two to three years from then on. The 2003 census recorded a decline to 90 wombats, as a result of the dingo predation in 2000. The 2007 hair census counted 138 wombats. The DNA analysis results from the 2010 hair census have not yet been finalised and released by EHP, however, based on the evidence of breeding at Epping Forest it is thought that there are around 150 wombat there. If you include the 12 wombats at the Richard Underwood Nature Refuge (RUNR), things are looking good for the northern hairy-nosed wombat. There have been several sightings of wombat joeys at Epping Forest and two births have been recorded at the new colony at RUNR.

This new colony at RUNR began with the first individual being flown from Epping Forest in 2009. Neil was his name – named after Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, because he was flown down on the 40th anniversary of the moon landings, on July 21 2009. After Neil’s arrival, 14 more wombats followed over a period of 13 months, travelling by plane – dubbed The Wombat Express – and by road.

The pitter patter of little feet at RUNR – along with new young viewed at Epping Forest – has heralded a major success for the Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat Recovery Plan. The first RUNR joey ventured out of its burrow in early October 2011 and was captured on video frolicking at the burrow entrance. The second joey appeared only a week later. The news caused quite a commotion and celebration among wombat conservationists throughout Australia and the world.

In 2010, two very observant (and oh so lucky) caretakers at Epping Forest – Stephanie Clark and Wayne White – quite literally stumbled on a young northern hairy-nosed wombat in desperate need of help. Harriet, named by Stephanie and Wayne, was found huddled up in a small burrow, far away from any burrow systems. At first they thought it was a swamp wallaby, but when they pulled the small animal out they found a northern hairy-nosed wombat joey. She was in a bad way – incredibly dehydrated, distressed, with patches of fur missing and blisters on her feet.

Being wildlife carers, Stephanie and Wayne knew what to do and first aid was provided. Once settled, Harriet was sent to Tina Janssen who cared for Harriet until release. Harriet was later renamed Princess Hobo as she turned out to be a true ‘little miss’, as is the wombat way! Harriet, AKA Princess Hobo, was successfully released at RUNR.

With two separate colonies established, the northern hairy-nosed wombat is now protected from disasters such as drought, fire and disease – which was a concern when only the one colony at Epping Forest existed.

Organisations such as the Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia and The Wombat Foundation are helping to raise awareness of the northern hairy-nosed wombat. The Wombat Foundation held its inaugural ‘Hairy-Nosed Day’ on May 11, 2012. On Hairy-Nosed Day, which will be a yearly event, schools are invited to pitch in to help save the endangered species by wearing hairy noses and collecting donations that will directly aid the conservation of the northern hairy-nosed wombat.

Southern hairy-nosed wombats

The southern hairy-nosed wombat is not as well protected as its northern cousin. Although greater in number there are many threats that face the southern wombat: land clearing, farming and competition with domestic stock, predation, roadkill and injury, disease and illness, introduction of pest species and – rather disturbingly – human persecution.

In South Australia there are several isolated pockets that are home to the southern hairy-nosed wombat, namely the Nullarbor Plain and Far West, the Eyre Peninsula, the Gawler Ranges and the Murraylands, with smaller colonies dotted around Yorke Peninsula in SA. Southern hairy-nosed wombat can also be found in the south-eastern corner of WA which makes up part of the Far West colony.

The Murraylands and Far West regions are the main strongholds for the southern hairy-nosed wombat and are considered to be ‘continuous populations’ whereas the Yorke Peninsula has 34 smaller, isolated colonies with an estimated count of about 690-odd individuals, as tallied in studies conducted by Dr Elisa Sparrow and the University of Adelaide from 2006 to 2008.

As with the once single colony of northern hairy-nosed wombat (before the RUNR translocation) these smaller isolated pockets of southern hairy-nosed wombat are under serious threat from fire, drought and disease.

In recent times the debilitating and often fatal disease called ‘sarcoptic mange’ has entered colonies of southern hairy-nosed wombat. As a relatively new disease, sarcoptic mange has created havoc in many southern hairy-nosed wombat populations. It is thought that the bare-nosed wombat has – over many years – built up some resistance to the disease, however the southern hairy-nosed wombat has been hit hard and local populations have been decimated.

Similarly, another new disease discovered by the Wombat Awareness Organisation (WAO) of SA in mid 2011 has done great damage to the status of the southern hairy-nosed wombat. WAO estimates that 70% of the Murraylands southern hairy-nosed wombat population has been affected by this dreadful, mysterious disease.

Dr Wayne Boardman and Dr Lucy Woolford, vets with Adelaide University, are researching the disease. Initially it was thought it was a fungal infection, however it is now thought to be a toxic liver disease, brought on by the ingestion of potato weed. This weed is site-specific, meaning not all populations are likely to be impacted, but it is only a new disease and much more research needs to be done.

Potato weed, which was introduced to southern Australia in the 19th century and has since spread across most of the continent, contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), chemicals that protect them from insects but which can be fatal or dangerous to many animals.

Once an individual shows signs of the disease, the downward slide is rapid. Onset symptoms are fur loss, then malnutrition and finally organ failure. Many wombats have died, although many were saved by the quick actions of WAO and other organisations.

Good southern hairy-nosed wombat habitat is now hard to find. Some landowners view the wombat as pests as burrows are often dug within productive farmland and so wombats are eradicated or dispersed into areas of not so favourable land with little food, water or suitable soil for digging burrows.

It is heartening to see that not all landowners think this way. Dr Elisa Sparrow conducted a statewide survey in 2011 and 2012, and whilst some landowners saw wombats as a nuisance or pest, more than 80% of landowners believe wombats should be conserved and believe coexistence between landowners and wombats is possible.

The Natural History Society of South Australia (NHS) is one conservation organisation that is purchasing good habitat where the wombats are protected. Portee Station near Blanchetown in the Murraylands district is one such parcel of land. At Portee Station, 2020 hectares purchased by NHS is now protected and wombats have been thriving in the good quality habitat. Established in 1968, the reserve is called Moorunde, explorer Edward Eyre’s name for the area. (Eyre was the first European who, along with his Aboriginal friend Wylie, crossed from South Australia to Albany in WA, across the Nullarbor Plain, on foot in 1840-41). An additional 6900 hectares of land surrounding Moorunde has since been purchased by NHS and a 50km long wildlife corridor now exists in the region. It is thought that there are around 2000 individual southern hairy-nosed wombats living on the extended Moorunde reserve.

Sadly, due to dry conditions of late, the habitat and grass cover at Moorunde and Portee Station has deteriorated somewhat. Potato weed and other weed cover, together with over-grazing by other species such as kangaroos, has left very little edible grass for the wombats and they are forced to eat unfamiliar species like the deadly potato weed, which is causing the often fatal toxic liver disease.

The Natural History Society of SA is now reseeding native grasses at Moorunde with the help of volunteers. They are also allowing some areas to regenerate by enclosing them.

The most disturbing news for the southern hairy-nosed wombat is human persecution. Some landowners view wombats as pests and their burrows are considered a huge inconvenience. Burrows are ploughed over by some landowners – trapping live wombats deep within the burrow systems. These wombats are doomed to die a slow and painful death without air or food.

Bob Irwin along with volunteers from WAO made news headlines in 2010 when they entered land to reopen some ploughed burrows. Wombats were seen and heard by Bob and his team within these burrows – even young joeys were seen! Unfortunately, it would seem that wildlife authorities in the area do little to combat this cruel and inhumane practice of ‘controlling’ wombats and it is still known to happen today.

To help combat this problem WAO initiated the Wombat Mitigation Project, a program to help landowners co-exist with wombats by developing and implementing viable alternatives to wombat culling. The Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia supports WAO in its work.

The Conservation Ark and Zoos SA are also working to save the southern hairy-nosed wombat from decline. Wombat Musters, headed by Dr Elisa Sparrow and Dr David Taggart, are regularly conducted with the help of eager volunteers. Wombats are captured, tagged, weighed, and data such as sperm is collected before the animals are returned back to the wild. Data collected from the musters help manage populations as well has monitor the impacts of climate change on the species. Data from these SA studies is also used to help conservation efforts for the northern hairy-nosed wombat.

For the last two years Dr Elisa Sparrow has been running Wombat Workshops in all the southern hairy-nosed wombat regions – eight workshops in total. These workshops were funded by the South Australian Government which wants to understand all the wombat issues, from all sides, statewide.

To conserve the southern hairy-nosed wombat long-term everyone needs to work together and communicate openly – researchers, conservation groups, landholders, government – for it to be most effective.

Bare-nosed wombats

Lastly, and by no means the least, is the best looking of the three species – the bare-nosed wombat. The bare-nosed wombat is classified as common and at no risk. But, if you ask any wombat conservationist what they think and chances are they’ll say it’s the wombat species most in trouble.

Its old name of ‘common wombat’ gave the impression that it is a common animal and numbers are in abundance, which may have been the case several years ago, but not today. At a Fauna First Aid wombat care course in southern NSW – which had several members of the Wombat Protection Society of Australia present – participants unanimously voted in the new name of bare-nosed wombat and we urge everybody to use this name and turn away from the inappropriate ‘common’ name and the misleading connotations it presents.

The bare-nosed wombat is facing threats at every level. It’s the southern hairy-nosed wombat story repeated but tenfold – land clearing, farming and competition with domestic stock, predation, roadkill and injury, disease and illness, introduction of pest species and, again, human persecution.

Although protected in NSW, culling permits are easily obtainable – ironically, it’s easier to get a wombat culling permit than a carer’s permit. In Victoria there are some parishes where a culling permit isn’t even required.

Roadkill and injury are other big threats. The wombat’s greatest sense is smell and danger is often perceived by smelling predators, etc. A road vehicle has no smell, at least not until it is quite close, and by that time it’s too late, the wombat doesn’t react in time and is hit.

The biggest threat in most areas where the bare-nosed wombat can be found is sarcoptic mange. It is thought that the mite that affects wombats – often fatally – is called Sarcoptes scabiei var. wombati; however there have been no DNA tests to prove this – it may well be the canine variety of Sarcoptes scabiei that also infests wombats.

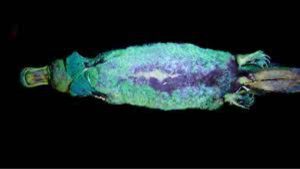

The irritation caused by the mite burrowing under the skin causes the wombat to scratch incessantly which in itself causes often irreparable damage to the skin including mutilation and hair loss. From the constant scratching, skin layers are taken off and raw flesh is exposed. The blood serum seeps through the mites’ tunnels to the exposed flesh, creating wounds and scabs. Ulcers and deep lesions develop which then cause secondary infection and blowfly strike.

Other visible symptoms of this disease are skin thickening and crusting over the body, including the eye and ear areas, causing blindness and deafness. The animal becomes too weak to search for food and malnutrition and dehydration follow. The immune system becomes depleted and the wombat looks emaciated.

In its advanced stages sarcoptic mange also has a devastating effect on internal organs, including the heart, liver, kidneys, lungs and reproductive organs. Respiratory infections and pneumonia can deplete the wombat further. Left without treatment, a wombat with sarcoptic mange will die – death is slow and painful.

Roz and Kev Holme of Cedar Creek Wombat Rescue (CCWR) at Central Mangrove (NSW) have been caring for wombats for several years and have a continual stream of mange-affected wombats passing through their gates. CCWR also carry out treatment regimes on wild-living wombats. It seems that mainly females without joeys are received into care more regularly, as wombats in this condition don’t breed. Sadly, if mange is contracted by a female with a joey she will often reject it as she can’t cope with the extra burden, so CCWR tend to keep an eye out for abandoned wombat joeys in the area.

Entire colonies of the bare-nosed wombat are being lost to this horrible disease; however an affected wombat can completely recover if it is treated early. You can help save these animals by reporting cases to your local wildlife organisation or to your local National Parks and Wildlife Service office. Record the time and exact location of the wombat so that it can be found easily by a ranger or wildlife carer.

The Wombat Protection Society of Australia, with the help of its members, is currently researching sarcoptic mange and they believe this disease can be reversed that many wombats can be saved. The Wombat Awareness Organisation is also working on mange in the southern hairy-nosed wombat populations of SA and has implemented a conservation project for wombats.

The Wombat Protection Society of Australia has designed a ‘self-applicating’ pesticide device that can be installed above a burrow, eliminating the need of handling wild wombats which can be distressing to the wombat. Wombat Protection will also send out free treatment kits to landowners, along with tips on how to treat wombats in the wild. Remember – the quicker you act the more chance a wombat has of survival.

How you can help

Please help to save all our wombats! Below are contact details of those who are working to protect and save wombats.

Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia, PO Box 42, Brighton Le Sands, NSW 2216; phone (02) 9556 1537; www.wpsa.org.au

Qld Department of Environment and Resource Management Wombat Survival Fund, PO Box 3130, Red Hill, Qld 4701.

http://www.ehp.qld.gov.au/wildlife/threatened-species/endangered/northern_hairynosed_wombat/index.html

The Wombat Foundation, GPO Box 2188, Sydney, NSW 2001; www.wombatfoundation.com.au

Wombat Protection Society of Australia, PO Box 6045, Quaama, NSW 2550; phone (02) 6493 8245; www.wombatprotection.org.au

Cedar Creek Wombat Rescue, PO Box 538, Cessnock, NSW 2325; phone 0429 482 551; www.cedarcreekwombatrescue.com

Zoos South Australia Conservation Ark, Dr Elisa Sparrow; phone (08) 8230 1321; www.conservationark.org.au

Wombat Awareness Organisation, PO Box 228, Mannum, SA 5238; phone 0458 737 283; www.wombatawareness.com

Natural History Society of SA, 3 Powell Court, West Lakes, SA 5021; www.nathist.on.net/index.shtml

Thanks to the following for sharing information and photographs for my presentation: Todd Woody; Stephanie Clark and Wayne White; Dr Alan Horsup, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection; Dave Harper, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection; Bob Irwin; Natural History Society of Australia; Wombat Awareness Organisation; Ann and David Howard; Roz Holme, Cedar Creek Wombat Rescue

Thanks to the following for helping me write this presentation: Dr Elisa Sparrow, Conservation Ark; Dr Alan Horsup, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection; Fiona Saxon (my sister), for her awesome editing skills.